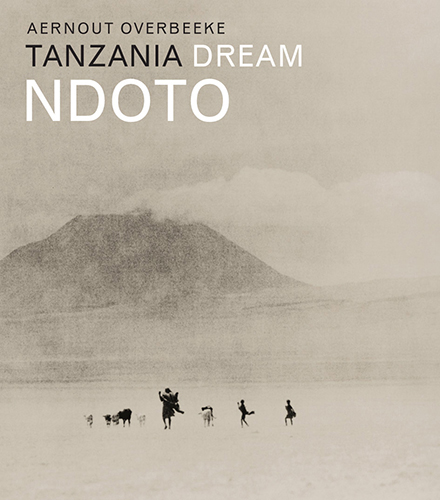

Ndoto, Tanzania Dream

Photos: © Aernout Overbeeke

Texts: © Pim Milo, 2010

In 1952, a year after Aernout Overbeeke’s birth, his family moved from Utrecht to Rotterdam, where Aernout’s father became editor-in-chief of the local edition of the daily newspaper Het Parool. When the family moved again, this time to Amsterdam in 1963, Aernout had already picked up an unmistakable Rotterdam accent, which put him at a disadvantage vis-a-vis his schoolmates. Although he would eventually acquire standard educated Dutch, he was isolated throughout his entire period at school. Instead of spending his time with his classmates and children from the neighbourhood, he spent all his free time in the Rijksmuseum and the Stedelijk Museum. In those formative years he studied art history on his own. They turned him into an obsessive viewer. Overbeeke left secondary school before completing his education and became a freelance photographer. For almost a year he was an assistant with Ed van der Elsken. Because he enjoyed seducing girls with his camera, he decided to become a fashion photographer. At the time there was hardly any fashion industry of its own in the Netherlands, and - apart from the trend-setting monthly Avenue - there was little innovation in the fashion photography of the magazines. Overbeeke gradually came to realise that his talent could not flourish here. After the birth of his children - a son Kenzo in 1978 and a daughter Teska in 1980 - he had to change course. The time had come to earn a living.

In 1952, a year after Aernout Overbeeke’s birth, his family moved from Utrecht to Rotterdam, where Aernout’s father became editor-in-chief of the local edition of the daily newspaper Het Parool. When the family moved again, this time to Amsterdam in 1963, Aernout had already picked up an unmistakable Rotterdam accent, which put him at a disadvantage vis-a-vis his schoolmates. Although he would eventually acquire standard educated Dutch, he was isolated throughout his entire period at school. Instead of spending his time with his classmates and children from the neighbourhood, he spent all his free time in the Rijksmuseum and the Stedelijk Museum. In those formative years he studied art history on his own. They turned him into an obsessive viewer. Overbeeke left secondary school before completing his education and became a freelance photographer. For almost a year he was an assistant with Ed van der Elsken. Because he enjoyed seducing girls with his camera, he decided to become a fashion photographer. At the time there was hardly any fashion industry of its own in the Netherlands, and - apart from the trend-setting monthly Avenue - there was little innovation in the fashion photography of the magazines. Overbeeke gradually came to realise that his talent could not flourish here. After the birth of his children - a son Kenzo in 1978 and a daughter Teska in 1980 - he had to change course. The time had come to earn a living.The book European Photography, edited by Edward Booth-Clibborn, a collection of the best of applied photography, was published in 1981. It was the first in a series of four publications. Those books expressed the trend that was emerging in England at the time to stop advertising looking like advertising. This was the reason why art directors opted for feature photographers, for people who could slowly and meticulously compose their photographs with a large-format camera on 10 x 8 inch negatives. Slow photography was a response to the increasing pace of society. Large-format photographers like Barney Edwards, Denis Waugh, Kenneth Griffiths and Rolph Gobits were brought in to make ads look more like features than advertising.

This form of photography appealed to Overbeeke. He invested all his time and energy in mastering the finesses of this technique. While cameras were becoming more compact and the film emulsions more sensitive - and thus faster - Overbeeke carried a large-format camera on his back and crept under a black cloth to set up that slow, clumsy and archaic camera. The mirror image appears upside down on the matt glass. Overbeeke has proved to be a bohemian, indifferent to the progress of the 21st century. He showed his new work - carefully composed studies in form and colour - in 1988. He presented his autonomous photographs to Paul Meijer, art director of the GO/Needham advertising agency. Meijer was impressed and immediately gave Overbeeke a campaign for the Centraal Beheer insurance company. Henny van Varik, creative director of the Akkerman, Meijer and Van Varik agency, gave him a campaign for the Westland/Utrecht Hypotheekbank in the same year. Both campaigns won awards in the Art Directors Club of the Netherlands (ADCN) and Overbeeke’s reputation was made. The mid-1980s were an era of visual flair in advertising, and Overbeeke’s sense of aesthetics was perfectly in tune with the enthusiastic perfectionism of art directors like Béla Stamenkovits, Frans Hettinga, Gerard van der Hart and Hans Goedicke.

Goedicke praised Overbeeke for his unusual compositions, the striking angles that he dared to assume with his camera, and his striving for perfection, his creativity in finding solutions that raise the idea of the art director to a higher plane. On top of that, Overbeeke is unashamedly selfish. He only finds an advertising idea interesting if he can give it a twist of his own. ‘Nice concept,’ he says in talks with the advertising agency, ‘but l’m going to tackle it very differently.’ And if he does not get his wagy, he rejects the commission without pardon. Overbeeke will never become a real advertising photographer; after all, he is not interested in how advertising works. But he is a keen image-maker who can translate the idea of the art director into a breathtakingly perfect photograph with stopping power.

In his search for the ultimate image, Overbeeke does not limit himself to just one camera technique or just one theme. Besides taking large-format photographs (5 x 4 and 10 x 8 inches), he also makes use of medium and panorama format; besides photographing landscapes, he also photographs nature, cars, interiors and people, and makes portraits. He does so for the advertising world, but also for feature magazines (in 1988 he documented the Mississippi from source to estuary with a Linhof 6 x 17 Technorama for Avenue) and personal projects. The only limitation that he stubbornly imposes is his refusal to go digital. As long as negative material and photographic paper are available -imported by himself if necessary - he will continue to take analog photographs.

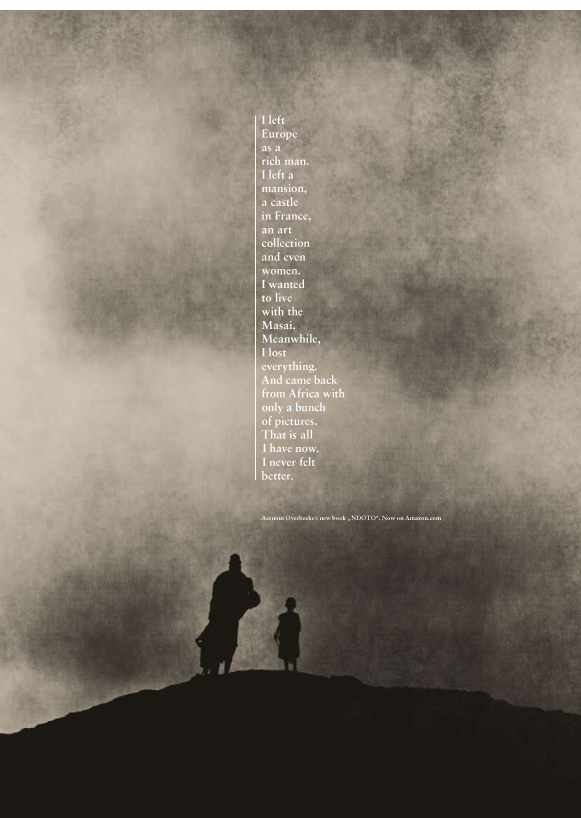

He saw potential in a disused orphanage, bought it, and turned the building into a genuine palace, as he was later to do again, but with a castle in the south of Burgundy, where he has lived like a god in France ever since. Imagination, perfectionism and the courage to take up the challenge: those are the three qualities that make Overbeeke a celebrated photographer.

There is interest in his talent abroad too. Aernout Overbeeke travelled through Australia for the Italian furniture firm Cassina in search of locations for the pieces. They were flown in by helicopter and very precisely placed on the designated spot. The contrast between the rugged landscape and the design furniture gives the pictures a Surrealist quality. The campaign is a textbook example of Overbeeke’s extreme perfectionism and the lack of compromise with which he works. A whole month went into the making of six photographs. These were one of the last large-scale photo productions of their kind. The year was 1991; Photoshop 1.0 had been on the market for a year. The art director who thinks up something like that today has to be satisfied with using a computer to assemble his images from the stock photos available on the internet.

In the meantime Overbeeke continued to look obsessively and to make personal photographs besides his commercial work, even when he was with a client and a dozen crew members in vans on location in California. ‘As a photographer I have a large responsibility and a lot is expected of me. As I drive through America, I see something terribly interesting and want to photograph it. In the past I would not have dared to in a situation like that. I’m well paid for the job and cannot permit myself to let my attention wander to something else. But now I stop the caravan and say: “Just practising with my finger to see if I can still do it.”’ He does not practise with a compact camera hanging from his neck and ready to shoot, but with a 6 x 9 Alpa camera which requires opening the boot of the car and unpacking the luggage - not snapshot photography but concentrated work. It is curious, because the loner Overbeeke does not like being surrounded by people, but at a moment like that he dares to ignore the peering glances of the people waiting behind him without scruples or nervousness.

At the outset of this new century Overbeeke started on a personal project for which he photographed actors and dancers in his studio, using objects from his large collection of ethnographic objects: masks, weapons and jewellery that he has brought back from his travels in Africa, Australia, Japan and former New Guinea. This project led him to travel to Tanzania and to document the Masai in their own biotope, driven by the desire to record for posterity a culture that is slowly but irrevocably losing its identity.

Overbeeke’s perfectionism does not stop once he has pressed the shutter. At home he has a darkroom which would make a professional lab jealous. He experiments there with developer and photographic paper. In the past his daughter Teska used to sit beside him on a stool, reading from a children’s book under the yellow lamp. By now she has become a photographer too.

The prints for Ndoto, Tanzania Dream were made by Overbeeke himself on baryta paper using a litho developer. The result is a graphic emulsion with extreme contrasts, maximal density, and a very high degree of sharpness of contour. With developer of this kind, the gamma increases with development time to a maximum and then drops again. The optimal development time is just before this maximum is reached. It is essentially a procedure intended for pure black-and-white work. If the paper is exposed beforehand, a very beautiful grey tint is produced that is just as long or short as Overbeeke wants, depending on the exposure time. It is a completely controllable process in which Overbeeke remains master of the material - just as he keeps everything under control to achieve perfection.